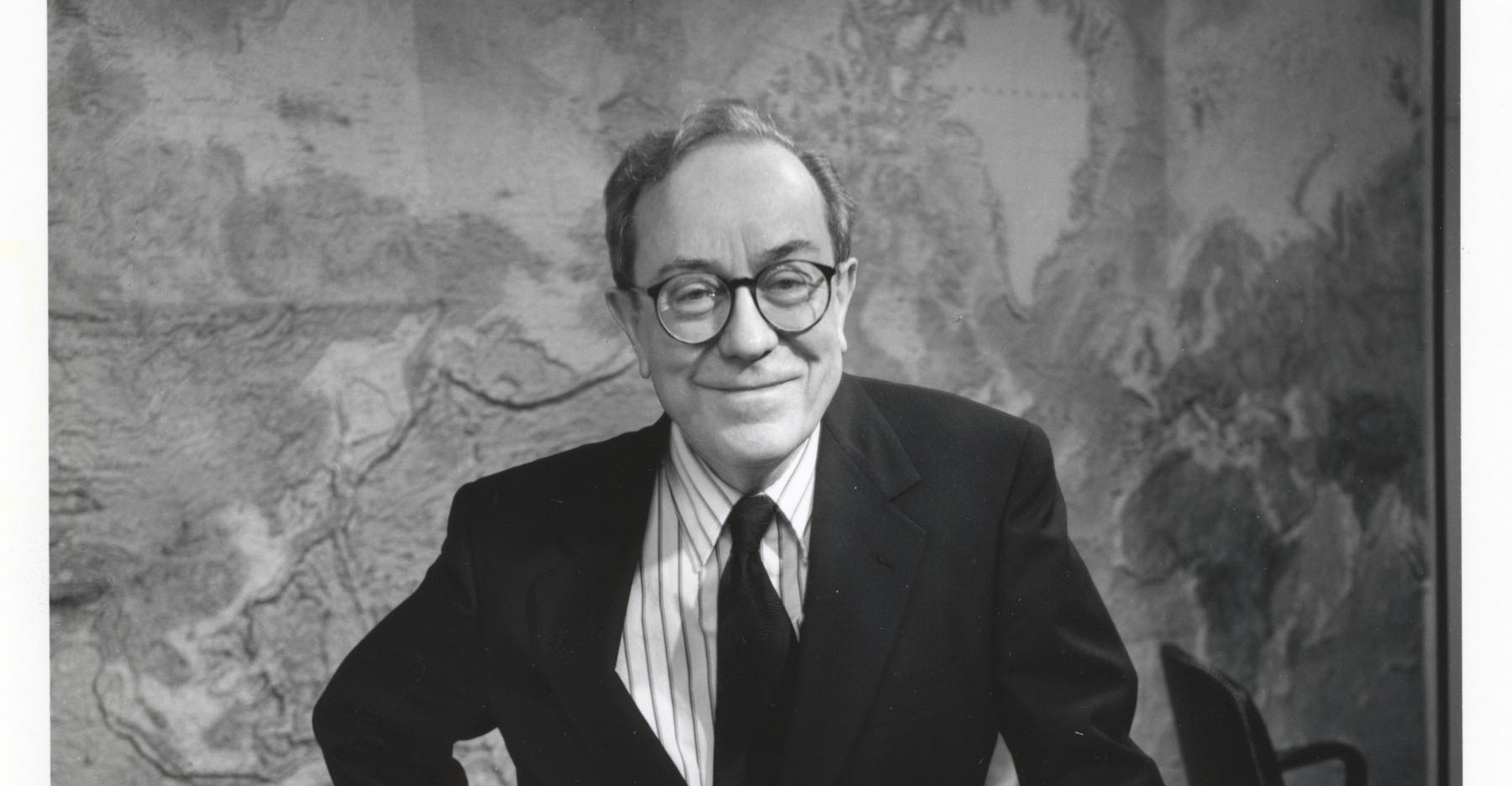

Photo: Jim Harrison

James Goodby

Public Policy

1st Heinz Awards - 1994

Ambassador James Goodby received the 1st Heinz Award for Public Policy. Virtually unknown to his countrymen or to the world, Ambassador Goodby is a quiet titan in the delicate, high stakes arena of international nuclear weapons negotiations.

Both the esoteric and security-sensitive nature of his specialty have required him to work almost entirely behind the scenes. But, for more than four decades under nine Presidents, James Goodby has made the world a safer place, beginning with his leadership of the effort to achieve a nuclear test ban treaty in the 1950s and 1960s. After retiring from the Foreign Service in 1989, Ambassador Goodby was called back in 1993 to serve as Chief U.S. Negotiator for the Safe and Secure Dismantlement of Nuclear Weapons. During his tenure, he negotiated over 30 agreements with several former Soviet Republics to assist in the dismantling of nuclear weapons, preventing weapons proliferation and converting military facilities to civilian enterprises.

Amb. Goodby came of age in the shadow of the atomic bomb. The post-war years - the late 1940s and early 1950s - saw the disintegration of wartime alliances and the escalation of East-West tensions. Goodby graduated from Harvard in 1951 and entered the Foreign Service in 1952. With the exception of the two years he served as U.S. Ambassador to Finland (1980-1981), most of his career dealt with international peace and security negotiations.

His reputation as a negotiator quickly spread through foreign policy and government circles. He was strong, dependable, smart, and, even more importantly, he seemed to have the knack for devising creative solutions to complicated questions. While assigned to the U.S. Mission to NATO in the early 1970s, he negotiated alliance positions on human rights and security provisions for the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, many of which became part of the Helsinki Final Act. After a stint as Vice Chairman of the U.S. delegation to the Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START), he became head of the U.S. delegation to the Stockholm Conference on Confidence and Security Building Measures and Disarmament in Europe in 1984. In that position, he negotiated the framework for negotiations on conventional force reductions in Europe. Former Secretary of State George Shultz, who describes Amb. Goodby as a “thoroughly laudable person,” has written that “Ambassador Goodby got the ball rolling very effectively, standing up to the Soviets, and rallying our allies.”

Praise for his accomplishments makes James Goodby, now a Distinguished Service Professor at Carnegie Mellon University, uncomfortable. A native New Englander, he modestly demurs: “Where I come from, we don’t feel comfortable with such talk... I had a lot of people to help me do it.”

It may surprise some that a single individual, bucking modern media worship by purposely evading publicity, could make such a difference to the fate of the world. But James Goodby - compelled to a life of public service by a desire to make the world a safer place - gives us all hope. Fortunately, there are still men and women who need nothing more than the inner satisfaction of a vision fulfilled and the knowledge that they have truly made a difference.

Note: This profile was written at the time of the awards’ presentation.